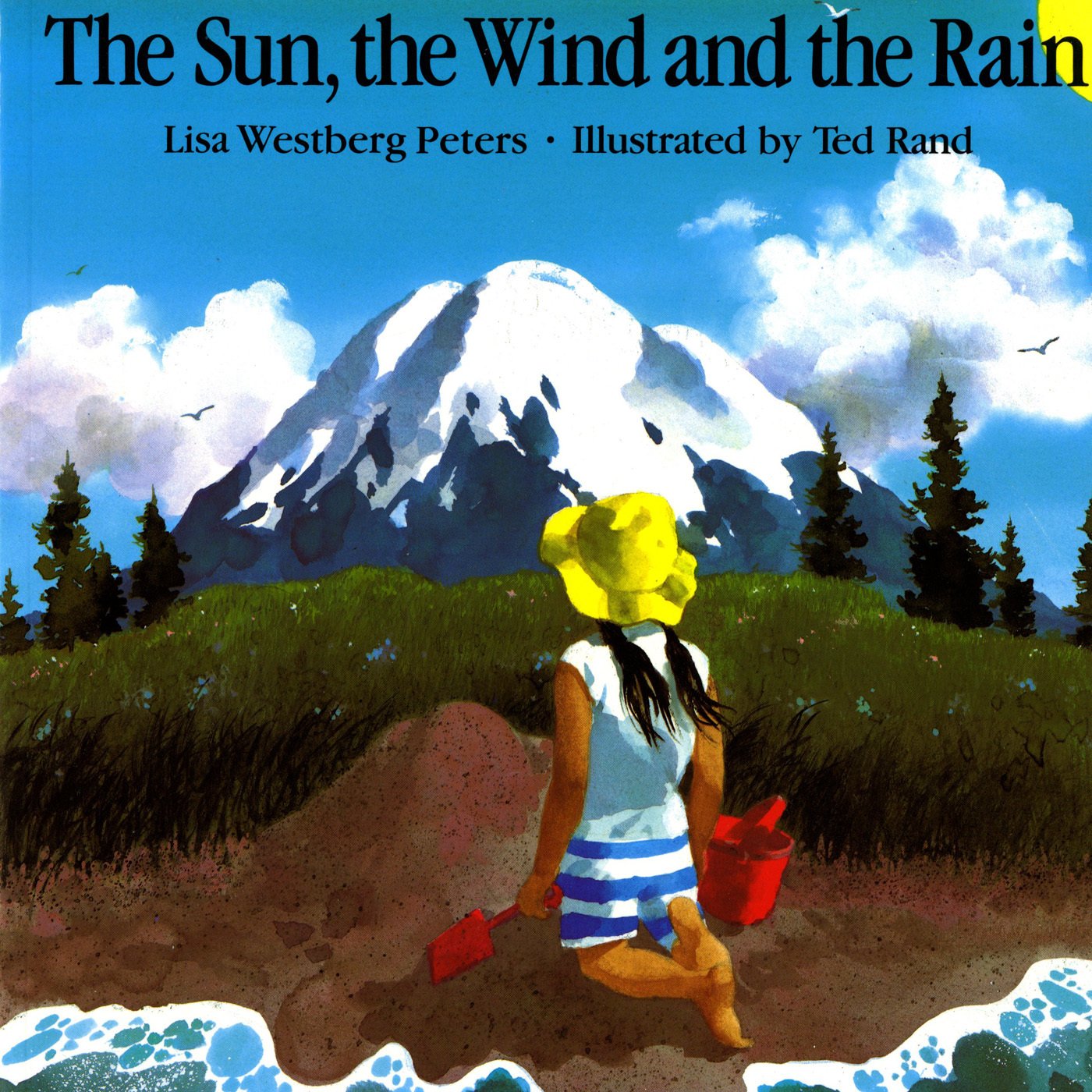

The Sun, the Wind and the Rain

This is the story of two mountains. The earth made one. Elizabeth in her yellow sun hat made the other.

Lisa Westberg Peters, illus. Ted Rand, Henry Holt, 1990.

32 pages, ages 4-8. ISBN: 0805014810

Awards & Recognition:

Nominated for a Minnesota Book Award

Washington Reads book list

Outstanding Science Trade Book

The Story Behind the Story

When my family and I were living in Seattle, I wanted to take an oceanography class (why not — I was living near the ocean), but it was full. I got into a geology class instead and loved it. I was especially struck by the idea that the earth’s crust is made up of recycled rock and sediment. I was also struck by the fact that mountains — huge, solid landforms — are not forever. They always wear down. I wanted to be the first to tell children of these discoveries.

My first story plan was to trace the journey of a quartz crystal. I sought help from a geology professor. He helped me identify a specific place in the Pacific Northwest that I could use as a reference, the Chuckanut Sandstone formation near Bellingham, Washington. My quartz crystal (it even had a name: Smoky) eroded out of a granite mountain. But personifying a crystal that was eventually buried by tons of sediment in the mountain building process turned out to be a big problem.

I changed the focus of the story to the mountain rather than the crystal, and introduced a child and her mother to increase the story’s appeal for children. And then I discovered that I could use the sun, the wind and the rain as symbols for change and the passage of time.

I introduced the parallel story structure — a child making a mountain and the earth making a mountain — to bring a difficult concept closer to a child’s level. At the time, my young daughter was more interested in sand piles than magnificent mountain ranges.

I revised the story many times and sent it around to publishers. It was rejected fifteen times. An editor at Henry Holt bought it, the very talented Ted Rand illustrated it, and it’s been in print ever since. It was given starred reviews, named an Outstanding Science Trade Book by the National Science Teachers Association and was selected for Washington Reads, an online book club for children. National Geographic plans to include it in the company’s electronic book reading series.

I still love the book.

Reviews

One for the Shelf/Riverbank Review, Summer 2001

Many writers attempt to produce creative science books for children, but few succeed. Books pumped full of whimsy have no weight, and books piled high with information rarely have a pleasing shape.

The Sun, the Wind and the Rain is a rare, creative science book with weight and a pleasing shape. The opening sentence gracefully describes it as “the story of two mountains.” The cover illustration shows a rounded, snow-capped peak and, at its base, a sandy mound built by a child. One is older, one is younger. One is large and one is small. “The earth made one. Elizabeth in her yellow sun hat made the other.”

And so begins a narrative about the way the earth builds mountains, originating with a molten pool, which cools and hardens and cracks and shifts. These grand events are pictured on the left side of the book, while on the right is a parallel tale of sand pushed up and shaped by energetic hands. Slowly on the one side, and quickly on the other, both mountains are eroded by the weather. Mountains, whether they are built by geologic thrust or by children, never last.

The text by Lisa Westberg Peters and the pictures by Ted Rand are in perfect accord, alive with action and detail. Gulls patrol the beach where Elizabeth plays, waves break, grasses blow—and ardently, ambitiously, Elizabeth devotes herself to nurturing her mountain. Her dazzling yellow hat attracts our attention throughout.

Author and artist have left Elizabeth alone—a daring choice. Nothing in the text suggests a playmate or a parent, and the artist doesn’t add them. In fact, there isn’t another soul in sight, which makes Elizabeth’s absorption in her play—or is it work–more striking.

Elizabeth appears to be alone, but even a child who is supervised—especially one who is engrossed in learning—may, at times, feel alone. This is the state of mind the book evokes: a deeply happy state of solitude, attentiveness, and wonder. It’s a state of mind essential to creative exploration, one that scientists share with children.

“It is not half so important to know as to feel,” Rachel Carson once said. Yet The Sun, the Wind and the Rain is a book that moves us all the more because it has a factual basis—a paradox that Carson would have savored. Peters planned the book while visiting the coast of Washington state, where mountains constantly erode onto beaches below. Rand also was attuned to this environment, which is his longtime home. Both did research for the book, but they could also see for themselves that a mountain of rock and a mountain of sand have a geological, as well as an aesthetic, link; the evidence lay splendidly before them.

The word erosion, by the way, is never used in the book. Avoiding definitions, Peters says a great deal indirectly and concretely. Her carefully developed scheme of using a child’s impulsive joy at digging in the sand to illustrate basic geologic change makes this an easy book to read. Sensory details—wet sand, fading light—make the story real.

Leaving the beach at the end of the day, Elizabeth climbs a winding trial. She brushes against a grainy wall, releasing sand that falls away, perhaps to form another mountain on another windy day. A changeable world invites a child to learn and grow, and mountains to begin.

-Mary Lou Burket

Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2001 Riverbank Review.

The Horn Book, 1988

With exceptional clarity of text and unusually appealing pictures, the geologic concept of mountain building is presented for young readers. “This is the story of two mountains. The earth made one. Elizabeth in her yellow sun hat made the other.” In brilliantly colorful double-page spreads, we follow the formation of a mountain over millions of years. Meanwhile, in inset pictures, we follow Elizabeth in a day at the beach where she piles bucketsful of wet sand to build a mountain. Wind and rain wear both mountains down. Eventually, the sandstone layers of the earth’s mountain shift and crack and are pushed up into a new mountain while Elizabeth uses the hard-packed sand after a rainstorm to rebuild her mountain. At the end of the day she leaves the beach and climbs a steep path. As she looks back, we see that her sandy beach is part of the sandstone mountain whose evolution we have been following. The two stories parallel each other perfectly, and the line of Elizabeth’s small sand mountain in the inset pictures flows seamlessly into the contours of the larger mountain. Both author and illustrator used the Chuckanut Mountain in northwest Washington as the geological model for the book.

Copyright © 1988 The Horn Book, Inc. All rights reserved.